Tuesday, 29 March 2011

Friday, 25 March 2011

two men

Monday, 21 March 2011

instant city by Archigram

Instant City forms part of a series of investigations into mobile facilities which are in conjunction with fixed establishments requiring expanded services over a limited period in order to satisfy an extreme but temporary problem.

Instant City forms part of a series of investigations into mobile facilities which are in conjunction with fixed establishments requiring expanded services over a limited period in order to satisfy an extreme but temporary problem.[Instant City is] A research project based on the conflict between local, culturally isolated, centres and the well serviced facilities of the metropolitan regions. Investigating the effect and practicality of injecting the metropolitan dynamic into these centres by means of a mobile facility carrying the information – education – entertainment services of the city, extended through the establishment of this together with the national telecommunication network. The initial study for this project is to be published in May. Grant approval for the main stage is under negotiation at this time. This project is carried out in co-operation with the Architectural Association. The Systems Consultant is Professor Gordon Pask of Brunel University Department of Cybernetics; Audio Visual Consultants, Program Partnership; Film Consultant Dennis Postle of B.B.C. Television.

The illustration shows a possible configuration when the Instant City is attached to a declining industrial area. The structures used are known forms such as toweres as in building operations, air structures and converted commercial vehicles.

Archigram

The Notion

In most civilised countries, localities and their local cultures remain slow moving, often undernourished and sometimes resentful of the more favoured metropolitan regions (such as New York, the West Coast of the United States, London and Paris). Whilst much is spoken about cultural links and about the effect of television as a window on the world (and the inevitable global village), people still feel frustrated. Younger people even have a suspicion that they are missing out on things that could widen their horizons. They would like to be involved in aspects of life where their own experiences can be seen as part of what is happening.

Against this is the reaction to the physical nature of the metropolis – and somehow there is this paradox – if only we could enjoy it but stay where we are.

The Instant City project reacts to this with the idea of a `travelling metropolis’, a package that comes to a community, giving it a taste of the metropolitan dynamic – which is temporarily grafted on to the local centre – and whilst the community is still recovering from the shock, uses this catalyst as the first stage of a national hook-up. A network of information-education-entertainment –‘play-and-know yourself’ facilities.

In England the feeling of being left out of things has for a long time affected the psychology of the provinces, so that people become either overprotective about local things or carry in their minds a ridiculous inferiority complex about the metropolis. But we are nearing a time when the leisure period of the day is becoming really significant; and with the effect of television and better education people are realising that they could do things and know things, they could express themselves (or enjoy themselves in a freer way) and they are becoming dissatisfied with the television set, the youth club or the pub.

A Background to Archigram Work

With our notion of the robot (the symbol of the responsive machine that collects many services in one appliance), we begin to play with the notion that the environment could be conditioned not only by the set piece assembly but by infinite variables determined by your wish, and the robot reappears in the Instant City in several of the assemblies.

The planning implications of Instant City have emerged more and more strongly as the project has developed, so that by the time we are making the sequence describing the airship’s effect upon the sleeping town, it is the infiltrationary dynamic of the town itself that is as fascinating as the technical dynamic of the airship. Again we have to reflect on the psychology of a country such as England, where there is a historical suggestion that vast upheaval is unlikely. We are likely to capitalise on existing institutions and existing facilities whilst complaining about their inefficiency – but a country such as England must now live by its wits or perish, and for its wits it needs its culture.

A Programme Background

The likely components are audio-visual display systems, projection television, trailered units, pneumatic and lightweight structures and entertainments facilities, exhibits, gantries and electric lights.

This involves the theoretical territory between the ‘hardware’ (or the design of buildings and places) and ‘software’ (or the effect of information and programming on the environment). Theoretically it also involves the notions of urban dispersal and the territory between entertainment and learning.

The Instant City could be made a practical reality since at every stage it is based upon existing techniques and their application to real situations. There is a combination of several different artefacts and systems that have hitherto remained as separate machines, enclosures or experiments. The programme involved gathering information about an itinerary of communities and the available utilities (clubs, local radio, universities, etc) so that the ‘City’ package is always complementary rather than alien. We then tested this proposition against particular samples.

The first stage programme consisted of assemblies carried by approximately 20 vehicles, operable in most weathers and carrying a complete programme. These were applied to localities in England and in the Los Angeles area of California. Later, having become interested in the versatility of the airship, we came to propose this as another means of transporting the Instant City assembly (a great and silent bringer of the whole conglomeration).

Later we applied the method of the Instant City to proposals for servicing the Documenta exhibition at Kassel in Germany. By this time also there had developed a feedback of ideas and techniques between this project and our Monte Carlo entertainments facility.

A Typical Sequence of Operations (truck-borne version)

1. The components of the ‘City’ are loaded on to the trucks and trailers at base.

2. A series of ‘tent’ units are floated from balloons which are towed to the destination by aircraft.

3. Prior to the visit of the ‘City’ a team of surveyors, electricians, etc have converted a disused building in the chosen community into a collection-information and relay-station. Landline links have been made to local schools and to one or more major (permanent) cities.

4. The ‘City’ arrives. It is assembled according to site and local characteristics. Not all components will necessarily be used. It may infiltrate local buildings and streets, it may fragment.

5. Events, displays and educational programmes are supplied partly by the local community and partly by the ‘City’ agency. In addition, major use is made of local fringe elements: fairs, festivals, markets, societies, with trailers, stalls, displays and personnel accumulating on an often ad hoc basis. The event of the Instant City might be a bringing together of events that would otherwise occur separately in the district.

6. The overhead tent, inflatable windbreaks and other shelters are erected. Many units of the ‘City’ have their own tailored enclosure.

7. The ‘City’ stays for a limited period.

8. It then moves on to the next location.

9. After a number of places have been visited the local relay stations are linked together by landline. Community One is now feeding part of the programme to be enjoyed by Community Twenty.

10. Eventually, by this combination of physical and electronic, perceptual and programmatic events and the establishment of local display centres, a ‘City’ of communication might exist, the metropolis of the national network.

11. Almost certainly, travelling elements would modify over a period of time. It is even likely that after two to three years they would phase out and let the network take over.

12. As the Instant City study developed, certain items emerged in particular. First, the idea of a ‘soft-scene monitor’, a combination teaching-machine, audio-visual jukebox, environmental simulator, and, from a theoretical point of view, a realisation of the ‘Hardware/Software’ debate (which is still going on in our Monte Carlo work), as the notion of an electronically aided responsive environment. Next, the dissolve of the original large, trucked, circus-like show into a smaller and very mobile element backed by a wonderful, magical dream descending from the skies. The model of the small unit suggests two trucks and a helicopter as the carriage, with quick folding arenas and apparatus that can quickly be fitted into the village hall. Another stimulus was the invitation to design the ‘event structure’ for the 1972 Kassel Documenta, an elaborate art/event/theatre scene requiring a high level of servicing but a minimum of interference with the ‘open-air creative act’. The ‘Kassel-Kit’ of apparatus can therefore be considered as a direct extension of the original IC Kit.

Are we back to heroics then, with a giant, pretty and evocative object? The Blimp: the airship: beauty, disaster and history. On the one hand we were designing a totally unseen and underground building at Monte Carlo, and on the other hand flirting with the airborne will-o-the-wisp. The Instant City as a series of trucks rushing round like ants might be practical and immediate, but we could not escape the loveliness of the idea of Instant City appearing out of nowhere, and after the ‘event’ stage, lifting up its skirts and vanishing. In fact, the primary interest was spontaneity, and the remaining aim to knit into any locale as effectively as possible. For Archigram, the airship is a device: a giant skyhook.

Operationally, there were two possibilities. A simple airship with apparatus carried in the belly and able to drop down as required. Otherwise, a more sophisticated notion of a ‘megastructure of the skies’. Ron Herron’s drawings (ref) suggest that the ‘ship’ can fragment, and the audio/visual elements are scattered around a patch of sky. Once again, the project work of the group has picked up a dream of it own past – the ‘Story of a Thing’ made (almost) real.

We then built a model, which could hang out its entrails in a number of ways. This was the simpler ‘ship’, which reads with the scenario of a small town transformation. In the drawing with airship ‘Rupert’, a major shift in Instant City was first articulated: the increasing feeling for change-by-infiltration. The ‘city’ is creeping into half-finished buildings, using the local draper’s store, gas showrooms and kerbside, as well as the more sophisticated set-up. And there is a mysterious creeping animal: the ‘leech’ truck, which is able to climb up any structure and service from it: with the resulting possibility of ‘bugging’ the whole town as necessary. Gently then, the project dissolves from the simple mechanics or hierarchies of ‘structuring’ and like-objects. Just as did the Plug-In City: it sowed the seeds of its own fragmentation into investigations of a gentler, more subtle environmental thing.

Archigram, Edited by Peter Cook, Warren Chalk, Dennis Crompton, David Greene, Ron Herron & Mike Webb, 1972 [reprinted New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999].

Basento River Bridge, Potenza. Itália 1967-69. Sergio Musmeci

Wednesday, 16 March 2011

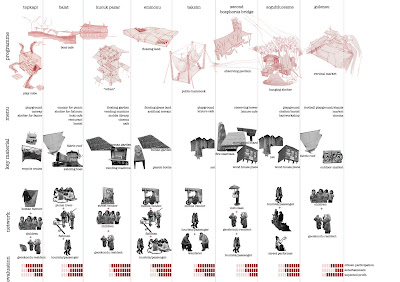

test of carnival network- sogutlucesme

test for carnival network-eminonu

test for carnival network-topkapi

The urban space along the old city wall in Topkapi is full of heterogenous elements and disconnections. Between the high speed motoway and the historic wall there are traditional bostan agriculture garden growing by migrants. Most of the farmers live right in the temporary shelters on the field.And the residents of the gecekondus inside the wall are difficult to access the outside by only a few gates along the hundreds of meters long wall. The wide green land and new city realm all seem far away from their life.

The urban space along the old city wall in Topkapi is full of heterogenous elements and disconnections. Between the high speed motoway and the historic wall there are traditional bostan agriculture garden growing by migrants. Most of the farmers live right in the temporary shelters on the field.And the residents of the gecekondus inside the wall are difficult to access the outside by only a few gates along the hundreds of meters long wall. The wide green land and new city realm all seem far away from their life.Monday, 7 March 2011

test of carnival network- Taksim Square

Friday, 4 March 2011

general introduction of Kartal's urban transformation project by Zaha Hadid

The Kartal – Pendik Masterplan is a winning competition proposal for a new city centre on the east bank of Istanbul. It is the redevelopment of an abandoned industrial site into a new sub-centre of Istanbul, complete with a central business district, high-end residential development, cultural facilities such as concert halls, museums, and theatres, and leisure programs including a marina and tourist hotels.

The site lies at the confluence of several important infrastructural links, including the major highway connecting Istanbul to Europe and Asia, the coastal highway, sea bus terminals, and heavy and light rail links to the greater metropolitan area.

The project begins by tying together the basic infrastructural and urban context of the surrounding site. Lateral lines stitch together the major road connections emerging from Kartal in the west and Pendik in the east.

The fabric is further articulated by an urban script that generates different typologies of buildings that respond to the different demands of each district. This calligraphic script creates open conditions that can transform from detached buildings to perimeter blocks, and ultimately into hybrid systems that can create a porous, interconnected network of open spaces that meanders throughout the city. Through subtle transformations and gradations from one part of the site to the other, the scripted fabric can create a smooth transition from the surrounding context to the new, higher density development on the site.

The soft grid also incorporates possibilities of growth, as in the case where a network of high-rise towers might emerge from an area that was previously allocated to low-rise fabric buildings or faded into open park space. The masterplan is thus a dynamic system that generates an adaptable framework for urban form, balancing the need for a recognizable image and a new environment with a sensitive integration of the new city with the existing surrounds.

Total Project Area: 555 Hectares (6 million square meters construction area)

Wednesday, 2 March 2011

Christiania in Copenhagen

Carnivalesque

Carnivalesque is a term coined by the Russian critic Mikhail Bakhtin, which refers to a literary mode that subverts and liberates the assumptions of the dominant style or atmosphere through humor and chaos.

Bakhtin traces the origins of the carnivalesque to the concept of carnival, itself related to the Feast of Fools, a medieval festival originally of the sub-deacons of the cathedral, held about the time of the Feast of the Circumcision (1 January), in which the humbler cathedral officials burlesqued the sacred ceremonies, releasing "the natural lout beneath the cassock."[1]

The Feast of Fools had its chief vogue in the French cathedrals, but there are a few English records of it, notably in Lincoln Cathedral and Beverley Minster. Today, carnival is primarily associated with Mardi Gras, a time of revelry that immediately precedes the Christian celebration of Lent; during the modern Mardi Gras, ordinary life and its rules and regulations are temporarily suspended and reversed, such that the riot of Carnival is juxtaposed with the control of the Lenten season, although Bakhtin argues in Rabelais and His World that we should not compare modern Mardi Gras with his Medieval Carnival. He argues that the latter is a powerful creative event, whereas the former is only a spectacle. Bakhtin goes on to suggest that the separation of participants and spectators was detrimental to the potency of Carnival.

In his Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics (1929) and Rabelais and His World (1965), Bakhtin likens the carnivalesque in literature to the type of activity that often takes place in the carnivals of popular culture. In the carnival, as we have seen, social hierarchies of everyday life—their solemnities and pieties and etiquettes, as well as all ready-made truths—are profaned and overturned by normally suppressed voices and energies. Thus, fools become wise, kings become beggars; opposites are mingled (fact and fantasy, heaven and hell).

Through the carnival and carnivalesque literature the world is turned-upside-down (W.U.D.), ideas and truths are endlessly tested and contested, and all demand equal dialogic status. The “jolly relativity” of all things is proclaimed by alternative voices within the carnivalized literary text that de-privileged the authoritative voice of the hegemony through their mingling of “high culture” with the profane. For Bakhtin it is within literary forms like the novel that one finds the site of resistance to authority and the place where cultural, and potentially political, change can take place.

For Bakhtin, carnivalization has a long and rich historical foundation in the genre of the ancient Menippean satire. In Menippean satire, the three planes of Heaven (Olympus), the Underworld, and Earth are all treated to the logic and activity of Carnival. For example, in the underworld earthly inequalites are dissolved; emperors lose their crowns and meet on equal terms with beggars. This intentional ambiguity allows for the seeds of the “polyphonic” novel, in which narratologic and character voices are set free to speak subversively or shockingly, but without the writer of the text stepping between character and reader